May 14, 2019

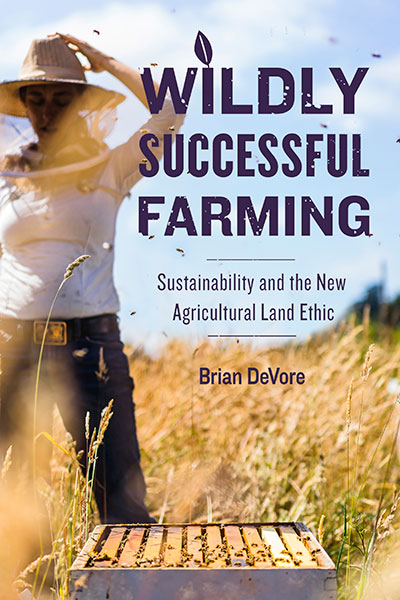

By Brian DeVore, Land Stewardship Project; author of Wildly Successful Farming

Tyler Carlson farms near “Gopher Prairie,” the fictional setting for Sinclair Lewis’s 1920 novel, Main Street. In the book, Lewis, who grew up in the real Gopher Prairie, otherwise known as Sauk Centre, Minnesota, used biting satire to poke fun at small town life. On a day that I visited the farm, Carlson was finding the havoc burrowing rodents were raising in his part of central Minnesota less than amusing.

“Some of the vision of this farm is really trying to make agriculture work alongside wildlife and wild ecosystems,” he said to me while examining a three-foot-tall white pine tree that was listing to one side in a pasture, its roots gnawed off by gophers. “But wildlife are pests in certain instances.”

That’s a harsh reality for someone who studied restoration ecology at the University of Minnesota before moving onto this 200-acre farm in 2012 to launch an operation that includes practices like “silvopasturing”—a system combining tree production with rotational grazing of livestock. Carlson saw silvopasturing as an economically viable way to re-build soil, combat climate change, and contribute to cleaner water, as well as support wildlife and pollinator habitat.

Seven years later, the farmer is still committed to producing ecosystem services, but reality checks like root-chomping rodents have tamped down his enthusiasm a bit, prompting him to readjust how he reaches his environmental goals while staying economically viable. Carlson has accepted the fact that farming with nature utilizing the principles of diversity, biology, and interdependence—rather than attempting to bring it to heel with iron, oil, and chemistry—means exposing oneself to a world that can be pretty unforgiving. This is the reality of being an “ecological agrarian,” someone who is unwilling to separate a working farm from a working ecosystem.

Ecological agrarians are using everything from managed rotational grazing and cocktail mixes of cover crops to the integration of native perennials and annual row crops to blend the wild and the domesticated on agricultural landscapes. Ideally, these kinds of farms strike a balance that provides practical benefits to the farmer while countering the negative repercussions of industrialized agriculture: dirty water, eroded soil, loss of wildlife habitat, and greenhouse gas emissions. A healthy soil ecosystem, for example, not only sequesters carbon, but allows farmers to better manage precipitation while providing free fertility for crops.

Ecological agrarians trust that a healthy ecosystem will eventually produce a healthy working farm. Some may argue that by placing their trust in the ways of the wild, these farmers are abdicating control over their own destiny in a way that’s no better (or is worse) than allowing human-centered technology to call the shots. But during my thirty years as an agricultural journalist who has interviewed a wide range of farmers, I have observed that ecological agrarians are continuously on the lookout for a better way—the opposite of being passive recipients of whatever life tosses their way. When a corn and soybean operation is reliant on petroleum-based inputs and technology developed in a biotech firm’s laboratories, events far from the land determine that farmer’s destiny. War in the Middle East can disrupt the flow of oil; yet one more consolidation in the biotechnology sector can limit the availability of affordable seed. But building a healthy, functional ecosystem starts and ends with a farm’s local terra-firma, literally from beneath the ground up.

Is ecologically-based agriculture sweeping across the landscape like some sort of new Green Revolution? Not by a long shot. In much of the Midwest, monocultural farming based on corn and soybeans still predominates. But ecological agrarians offer their conventional counterparts a chance to make their fields more resilient as they increasingly struggle with extreme weather and herbicide-resistant super-weeds.

The current buzz around building soil health by growing cover crops between the regular corn-soybean growing seasons can trace its roots, so to speak, to one of the most ecologically rich biomes known: the tallgrass prairie. A recent national survey on cover cropping showed that getting “continuous living cover” on the land 365 days a year produces environmental and economic benefits in a matter of a few short years. The prairie was the original form of continuous living cover. The latest Census of Agriculture shows that cover crops were recently planted on 15.4 million acres nationwide, an increase of fifty percent over a five-year period. Ecological agrarians, with their emphasis on utilizing biodiversity whenever possible, can be thanked for conventional agriculture’s recent interest in “mimicking nature” through cover cropping.

Indiana crop farmer Dan DeSutter once described to me how one day he was standing in a trench fixing a drainage tile line and noticed that roots from a rye cover crop were boring at least four feet deep into the soil. Such “bio-drilling” was impressive, given that over the years the DeSutters had been putting a lot of effort into using a mechanical ripper to break up soil compaction. Ripping requires a tractor with lots of horsepower and burns lots of fuel.

“That was my aha moment,” DeSutter told me. “We were spending all this money on ripping when for a few dollars per acre worth of seed, this plant would be doing it for us. You tell me what’s going to do it better: the plant or the steel?”

Of course, mimicking nature also means playing by its rules. Tyler Carlson and his partner Kate Droske’s Early Boots Farm has modified its silvopasturing system and made it, if not exactly ecologically pristine, at least a benefit to the environment. And the forage being produced by building soil health between the rows of surviving trees is good enough to consistently produce quality beef, which is important economically. On a farm where the borders between the wild and the tame are porous, opportunities for making mid-course adjustments abound. If injecting a little bit of woodland into a domesticated pasture doesn’t pan out, why not reverse polarity?

At one point, Carlson led me over a fence to an existing stand of bur oak, ash, ironwood, elm, and aspen. Invasive buckthorn had been set back considerably with the help of a chain-saw. In glade-like spots between trees, red clover and orchard grass Carlson had seeded were making use of the solar energy. For the past few years, this woodland has been a part of his rotational grazing system. Grazing among the trees isn’t as productive as running cattle through open pastures, but it is a low-impact way of attaining ecological goals in a financially viable manner. The cattle have a cool place to graze during hot weather while they help control buckthorn. Opening up the woodland hasn’t just benefited forages—recently Carlson noticed oak seedlings sprouting; in 2012, there were few oaks under seventy-five-years-old here.

This woodlot has been abused and neglected for over a century. But through the introduction of innovative farming practices that involve disturbance and rest, it is being revived as a key ecological component of a working landscape. Transplanting a little nature into tame pastures has been surprisingly difficult, but reversing things and introducing domesticated beasts into an unruly corner of the farm is paying off. A farm that has planted every last acre to corn and soybeans doesn’t have such flexibility when things go awry.

The bottom line: when the wild bites back, it doesn’t always hold a grudge. “It shows that if you let it, nature can be pretty forgiving,” said the farmer as he made his way among the trees in the dappled sunlight.